“How come you’re not wearing a sari?”

“There’s a new box of Non-Fiction books in the library!”

“Today is the sketch walk, no?”

“Which car did you bring?”

“I have 23 rupees for the library party!”

“Didi is not giving me the key—Didi!!!”

This was my welcome one morning. Not your typical “Good morning, Ma’am,” but something far richer and more vibrant.

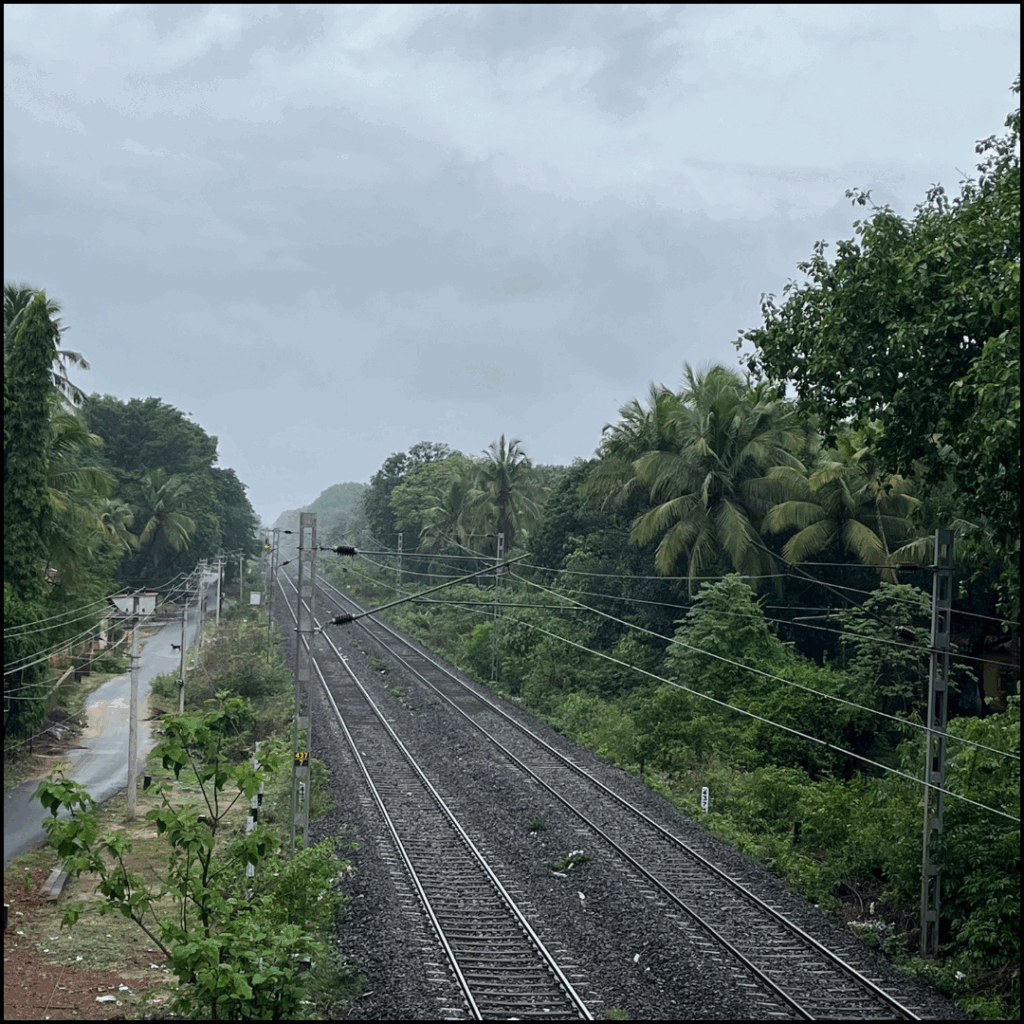

I’m in Seraulim—a village that’s technically a suburb of Margao, but very much a place with its own rhythms. A railway line cuts right through it, unguarded and constant. Just a kilometre away, the NH66 highway looms overhead, ready to funnel all kinds of goods through Goa. Seraulim is also neighbour to the industrial town of Verna. Here, like across India, the railway tracks are home to working-class settlements—communities that power Goa’s construction, tourism, and domestic industries.

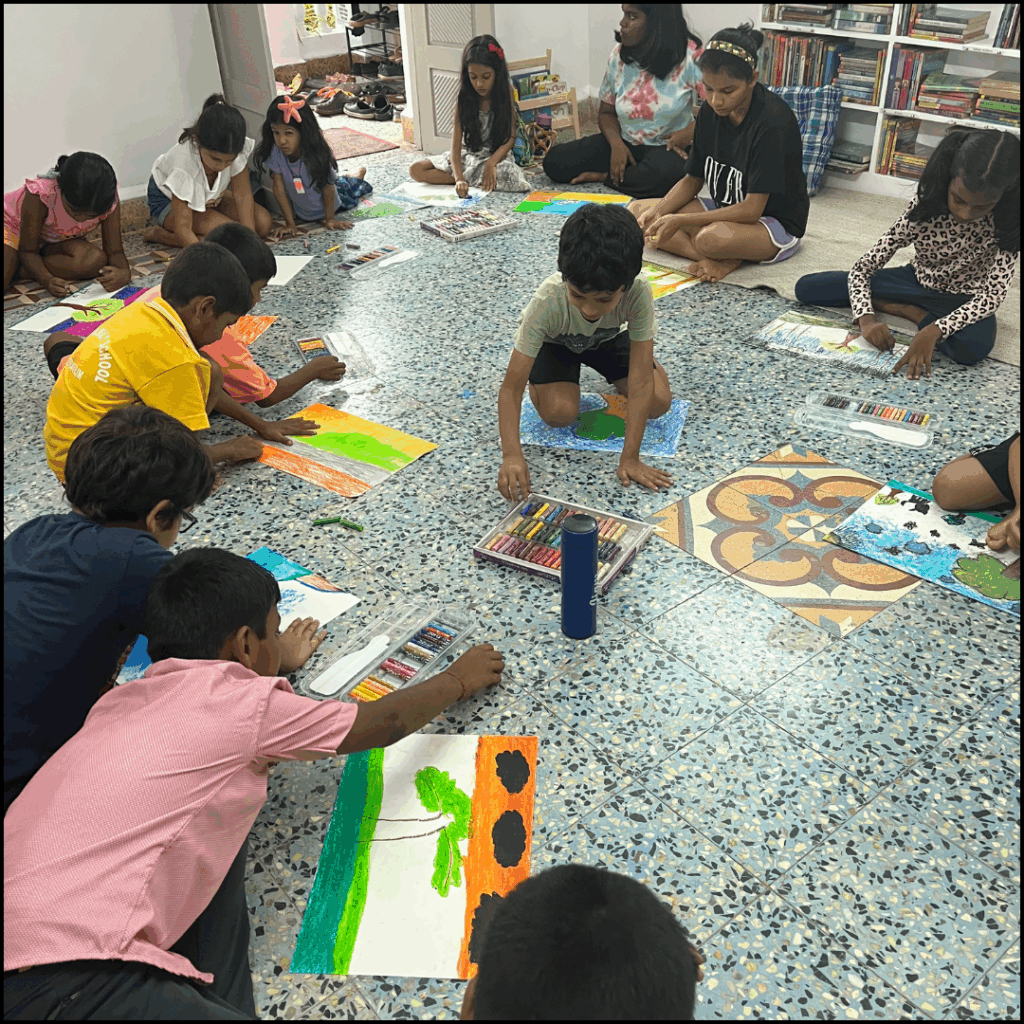

Our little library sits on a lane parallel to those tracks, sharing space with some beautiful homes. Only one child from those ‘elite’ houses visits us. The rest—regular, robust, and remarkable—come from working-class families. They’re in the library because of a circle of Bookworm friends who’ve helped make their presence possible. Every day, these children show me what learning, opportunity, and community can look like.

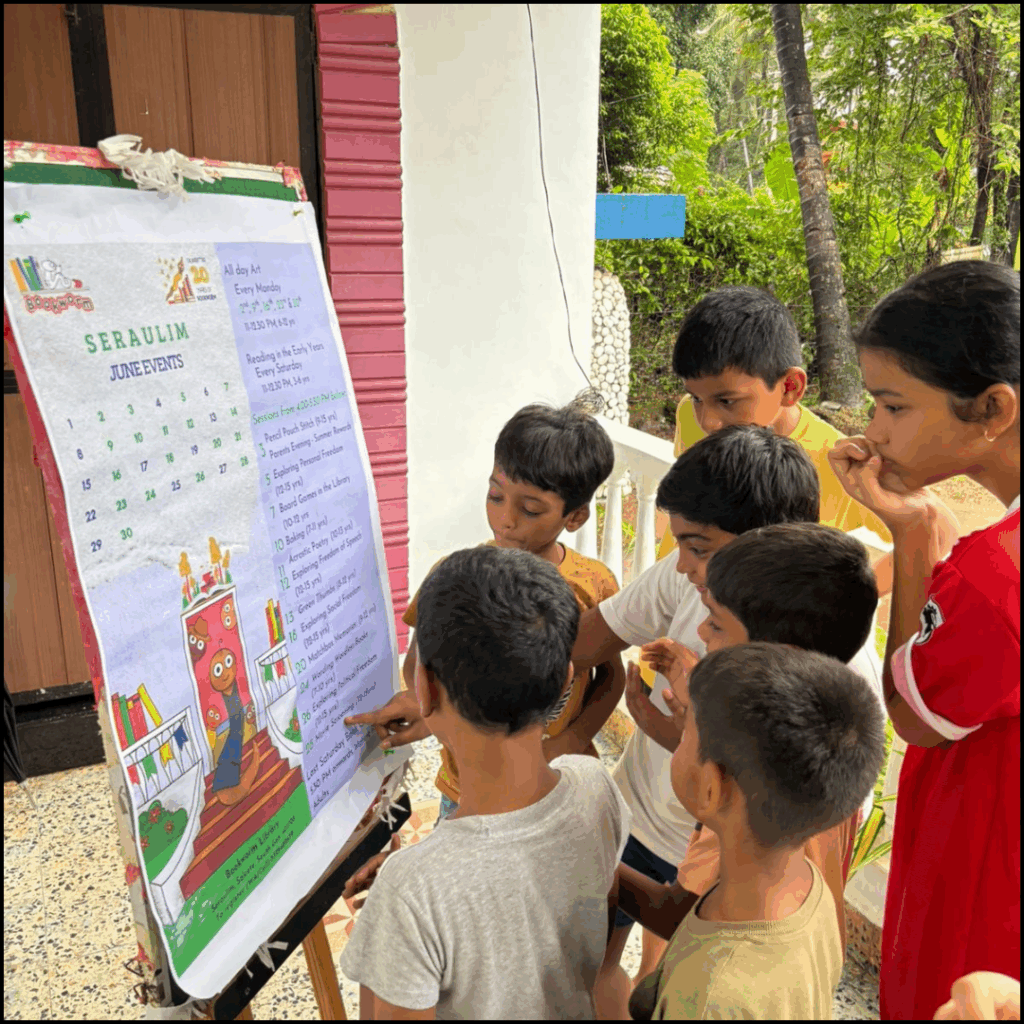

Reading a Calendar, and the World

As summer came to a close, I watched our core group of 10–12 children read the June calendar on the wall. Not just look at it—but really read it.

I often have to explain this kind of text to more formal literate parents or children. But not to these children.

“Hey, 28th June—Movie Screening. We must ask Sinead Miss what movie she’ll show.”

“Sujata, you’re doing stitching on June 3rd, right? I’ll come.”

“So many art sessions! Jolyan will lead them, right?”

“Samantha Miss? Hmm… maybe the Freedom sessions? We’ll see.”

They navigate this space with ease and energy. And as we look back on April and May, we’ve realised something powerful: an inclusive library has quietly nurtured a kind of agency we hadn’t fully imagined.

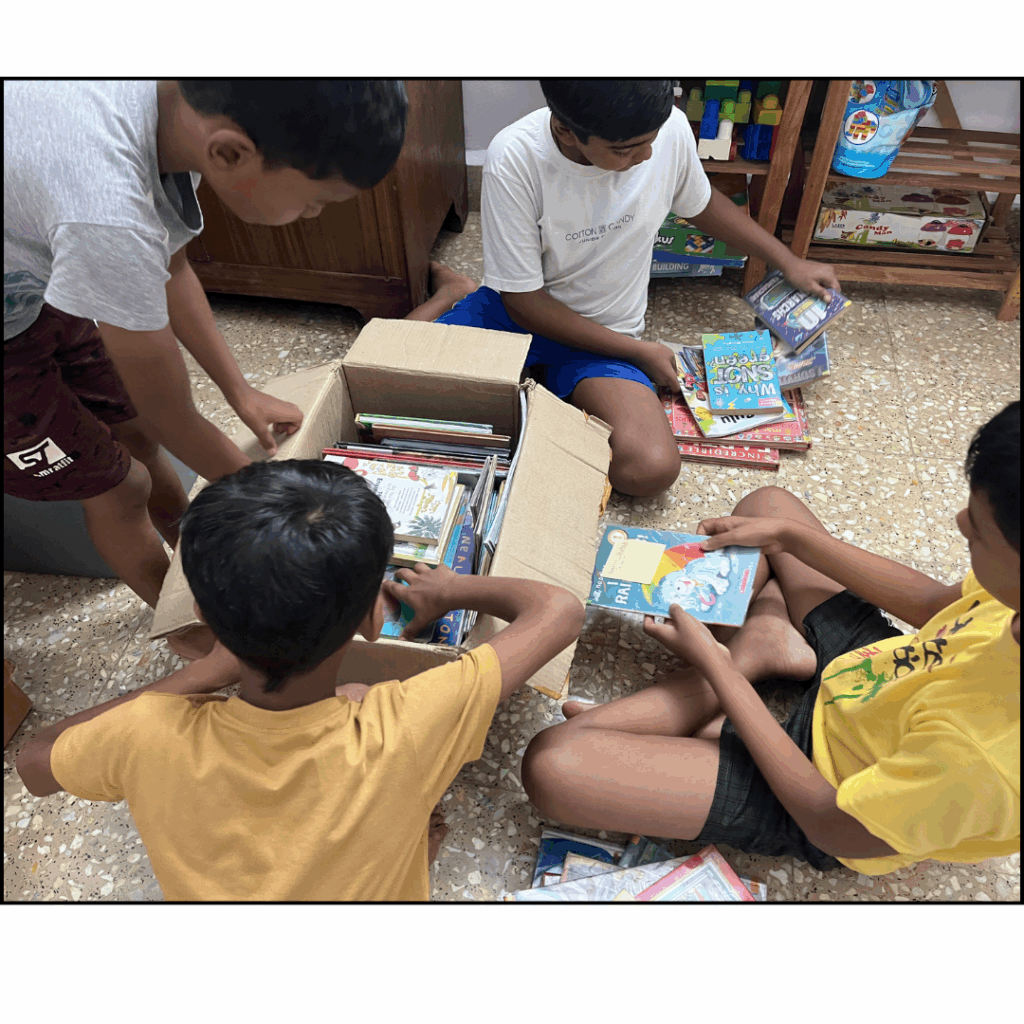

The Box of Non-Fiction

One day, a new box of Non-Fiction books arrived. The shelf had already been cleared. I asked, “Can you sort and shelve the books?”

“Yes!” came the enthusiastic response.

I watched from the next room as three young, first-generation library users untaped the box. Squeals of joy erupted as they pulled out book after book. Then one of them said, “Let’s sort by colour code.” And so, small piles began to form.

When I came in, I asked, “Is this how you learned to sort from Samantha Miss’s genre sessions?” No one answered—but the calm confidence in their work was all the response I needed.

Later, I was invited back. They had created categories: biographies (one they’d read in April was quickly set aside as “not new”), books on nature and the environment, subject-based books like Science, Geography, History, and even Math. I smiled when I saw books on shape, art, and puzzles nestled under the math section. One child held up a book about libraries and declared, “This should go on the thematic shelf—even though it’s Non-Fiction.”

They handwrote signs, affixed them, and shelved the books. I had done nothing. And as we admired this freshly organized shelf, one child said thoughtfully:

“We must tell Anandita Miss that there are no Fact-Fiction books in this selection.”

What Does It Really Take?

So little, really.

Just the consistent presence of a caring, knowledgeable adult. A summer calendar filled with engaging sessions. And a space that encourages trust, joy, and curiosity.

The children now maintain their library cards, return books diligently, and are beginning to request titles by topic. These are the seeds of becoming lifelong readers.

But as I looked through the lending data from April and May, I noticed something. The children who haven’t returned books, or whose visits have grown infrequent, are mostly from highly literate families.

What’s going on?

In this packed world of structured extracurriculars, are some children losing touch with the library?

And more importantly:

What do children miss when they don’t interact across class and caste lines?

The answer is: so very, very much.

In the library, they forget who’s who. They listen to each other’s stories. They partner—confident readers with new ones. They enter new worlds of thought that simply wouldn’t be possible in a segregated space.

This is how empathy and aspiration grow: through shared experiences on common ground.

So, What Now?

The question we’re now asking ourselves is this:

How do we bring in more children—from both sides of the railway tracks, and beyond?

Because the library is not just a building of books. It is a living, breathing space for equity, community, and imagination. And it’s teaching all of us how to be a little more human, every day.

So much to learn think enjoy. THanks a lot